Gravitational Wave Detector Simulator

Listen to the universe’s most violent events through ripples in spacetime itself

Detecting Einstein’s Waves: A New Window to the Cosmos

In September 2015, humanity opened an entirely new window to the universe. For the first time, scientists detected gravitational waves—ripples in the fabric of spacetime itself—from two black holes merging 1.3 billion light-years away. This detection confirmed Einstein’s 1915 prediction and revolutionized astronomy by allowing us to “hear” cosmic events invisible to light.

Our Gravitational Wave Detector Simulator lets you explore this groundbreaking science. Calculate strain sensitivities, analyze signal characteristics from different cosmic events, understand detector arm lengths, and simulate the kind of signals that LIGO, Virgo, and future detectors like LISA search for in the cosmic symphony.

What Are Gravitational Waves?

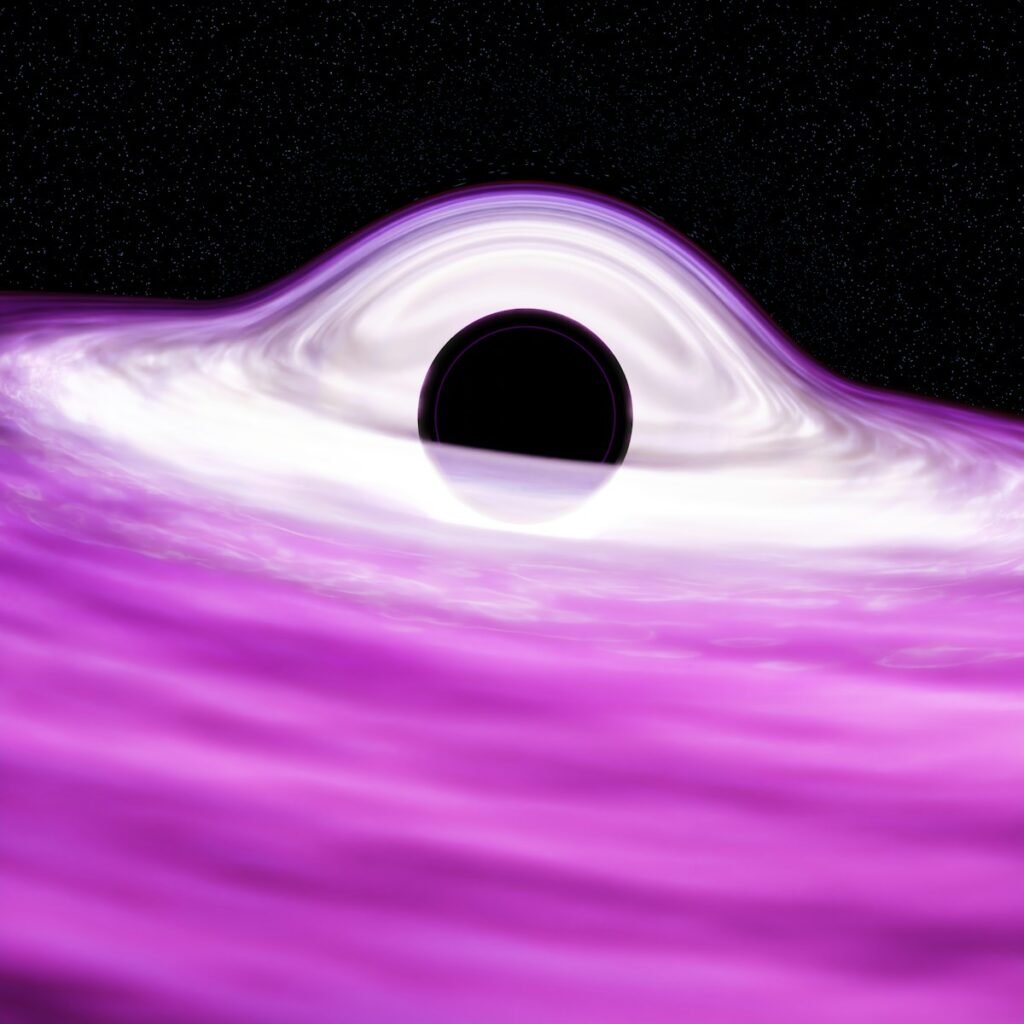

Gravitational waves are disturbances in spacetime caused by accelerating masses. According to Einstein’s general relativity, massive objects bend spacetime around them. When these objects accelerate—especially in violent events like merging black holes or neutron stars—they create ripples that propagate outward at the speed of light.

These waves stretch and compress space as they pass. However, the effect is extraordinarily tiny. Even from the most violent events in the universe, gravitational waves arriving at Earth change distances by less than 10⁻¹⁸ meters—smaller than a proton. Our Planck to Cosmic Time Calculator reveals how these measurements approach the quantum limits of space itself.

Gravitational Wave Detector Simulator

Simulate gravitational wave signals from cosmic events and explore detector physics:

🌊 Gravitational Wave Detector

Experience the ripples in spacetime caused by cosmic collisions!

🔬 What Are Gravitational Waves?

📅 Enter Your Birth Year

Simulate signals from binary black holes, neutron stars, supernovae, and more. Explore how detector sensitivity varies with frequency.

Understanding Gravitational Wave Detection

Gravitational wave detectors are among the most precise measuring instruments ever built. The LIGO detectors (Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) measure changes in distance smaller than 1/10,000th the width of a proton—an almost unfathomable precision achieved through laser interferometry.

Laser Interferometry: The Detection Method

LIGO uses two perpendicular arms, each 4 kilometers long. A laser beam splits and travels down both arms, bouncing off mirrors at the ends. When the beams recombine, any difference in path length creates an interference pattern. A passing gravitational wave stretches one arm while compressing the other, creating a detectable signal.

The strain (h) measures how much space stretches: h = ΔL/L, where ΔL is the length change and L is the arm length. For typical detections, h ≈ 10⁻²¹, meaning a 4km arm changes by about 10⁻¹⁸ meters. This precision seems impossible, yet multiple detections now confirm the technique works. Learn about the incredible energies involved using our Fusion Energy Calculator.

Sources of Gravitational Waves

Several cosmic events produce detectable gravitational waves:

- Binary Black Hole Mergers: Two black holes spiraling together produce the strongest signals. The first detection (GW150914) came from 36 and 29 solar mass black holes merging. Explore black hole physics with our Hawking Radiation Timer

- Binary Neutron Star Mergers: The 2017 detection GW170817 not only produced gravitational waves but also light, confirming neutron star mergers create heavy elements. Our Neutron Star Density Calculator explores their extreme properties

- Core-Collapse Supernovae: Asymmetric stellar explosions should produce gravitational waves, though none have been detected yet

- Continuous Sources: Rapidly rotating neutron stars with asymmetries emit constant gravitational waves

- Cosmic Background: The Big Bang may have produced primordial gravitational waves still echoing through the universe

The Gravitational Wave Open Science Center provides public data from all confirmed detections, allowing anyone to analyze these cosmic signals.

Current and Future Detectors

A global network of gravitational wave observatories works together to detect and localize cosmic events:

Ground-Based Detectors

LIGO (USA): Two L-shaped detectors in Louisiana and Washington State, each with 4km arms. Operating since 2015 with Advanced LIGO upgrades, achieving strain sensitivity of ~10⁻²³ at peak frequencies around 100-300 Hz.

Virgo (Italy): A 3km arm detector near Pisa that joined the observation network in 2017. Together with LIGO, it enables precise sky localization of gravitational wave sources—crucial for electromagnetic follow-up observations.

KAGRA (Japan): The first underground and cryogenically-cooled detector, located in the Kamioka mine. Its design reduces seismic noise and thermal fluctuations that limit other detectors.

Multiple detectors improve source localization. With two LIGO detectors, sources can be localized to a ring on the sky. Adding Virgo narrows this to patches of ~10-100 square degrees. More detectors mean faster alerts for follow-up telescopes. The timing precision rivals what our Speed of Light Delay Calculator reveals about signal travel times.

Space-Based Detectors

LISA (Laser Interferometer Space Antenna): Planned for launch around 2035, LISA will consist of three spacecraft forming a triangle with 2.5 million kilometer arms. This enormous baseline allows detection of low-frequency gravitational waves (0.1 mHz to 1 Hz) from supermassive black hole mergers and thousands of binary systems in our galaxy.

The scale of LISA is staggering—calculate the light travel time between its spacecraft using our Cosmic Distance Ladder. At such scales, even small gravitational wave signals produce measurable path length changes.

The Physics of Signal Detection

Understanding gravitational wave signals requires knowledge of both the sources and the detector limitations. The original LIGO detection paper describes the intricate analysis that confirmed GW150914.

Chirp Signals: The Fingerprint of Mergers

Binary inspirals produce characteristic “chirp” signals—frequencies and amplitudes that increase as the objects spiral closer. The chirp mass, calculated from the frequency evolution, reveals the combined mass of the system:

M_chirp = (m₁m₂)³/⁵ / (m₁ + m₂)¹/⁵

For GW150914, the chirp mass was about 30 solar masses, immediately indicating massive stellar-mass black holes. The final merger released about 3 solar masses worth of energy as gravitational waves—more power than all the stars in the observable universe combined, but lasting only milliseconds.

Noise Sources and Sensitivity

Detectors must overcome numerous noise sources:

- Seismic Noise: Earth vibrations dominate at low frequencies (<10 Hz). Multi-stage pendulum suspensions provide isolation

- Thermal Noise: Random molecular motion in mirrors and suspensions. Cryogenic cooling and careful material selection help

- Shot Noise: Quantum fluctuations in photon numbers limit high-frequency sensitivity. More laser power helps, but introduces radiation pressure noise

- Quantum Noise: The fundamental limit—squeezed light techniques push beyond the standard quantum limit

Understanding quantum limits connects to our Quantum Probability Visualizer, which explores the probabilistic nature underlying these measurements.

Discoveries and Scientific Impact

Gravitational wave astronomy has already transformed our understanding of the cosmos:

Black Hole Population: Before LIGO, stellar-mass black holes were inferred indirectly. Now we’ve directly detected dozens, revealing a population of surprisingly massive black holes (20-80 solar masses) that challenges stellar evolution models.

Multi-Messenger Astronomy: GW170817 (two neutron stars merging) was detected in gravitational waves and electromagnetic radiation simultaneously. This confirmed neutron star mergers as sites of heavy element nucleosynthesis—gold, platinum, and uranium are forged in these cosmic collisions.

Hubble Constant Measurement: Gravitational waves provide a new “standard siren” method for measuring cosmic distances, potentially resolving tensions in Hubble constant measurements. Our Redshift Calculator explores traditional methods.

Testing General Relativity: Each detection tests Einstein’s theory in extreme gravity regimes. So far, general relativity passes every test, but future detections may reveal deviations pointing to new physics.

The Future of Gravitational Wave Astronomy

Current detectors represent just the beginning. The Cosmic Explorer concept envisions 40km arm detectors with 10x better sensitivity than Advanced LIGO, capable of detecting binary black hole mergers throughout the observable universe.

The Einstein Telescope, planned for Europe, will use underground triangular geometry with cryogenic mirrors to push sensitivity limits further. These next-generation detectors could observe hundreds of mergers daily, creating a continuous stream of gravitational wave data.

Pulsar timing arrays like NANOGrav search for extremely low-frequency gravitational waves by monitoring millisecond pulsars across our galaxy. Recent results suggest a cosmic gravitational wave background from supermassive black hole binaries throughout the universe.

The ultimate goal: detecting primordial gravitational waves from the Big Bang, which would reveal physics from the first fraction of a second of cosmic history. Explore this earliest era with our Cosmic Timeline Explorer.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can gravitational waves travel faster than light?

No. Gravitational waves travel at exactly the speed of light, as predicted by general relativity and confirmed by multi-messenger observations. The near-simultaneous arrival of gravitational waves and gamma rays from GW170817 (within 1.7 seconds after traveling 130 million light-years) constrained any difference to less than one part in 10¹⁵.

Why can’t we feel gravitational waves from nearby objects?

Gravitational waves require enormous accelerating masses to produce detectable effects. Even Earth’s orbit around the Sun produces gravitational waves with strain of only ~10⁻⁴¹—trillions of times weaker than LIGO can detect. Only catastrophic events like black hole mergers release enough energy to create observable signals across cosmic distances.

How do scientists distinguish gravitational waves from noise?

Multiple detectors must see the same signal within light-travel time (about 10 milliseconds for LIGO’s separated locations). The signal must also match theoretical templates—chirp signals from binary inspirals have predictable frequency evolution. Statistical analysis determines confidence levels, with detections requiring less than one false alarm per 100,000 years.

Could gravitational wave energy be harvested?

In principle, yes—gravitational waves carry energy. In practice, the energy density is incredibly small. Even during the strongest detections, the power passing through Earth is only about 50 watts total—and extracting it would require a detector spanning the solar system. The energy released in mergers is vast but spreads over enormous spherical surfaces, arriving impossibly diluted.

Explore More Cosmic Phenomena

Gravitational wave astronomy connects to many aspects of extreme physics. Continue exploring with these related tools:

- Black Hole Calculator – Explore event horizons and black hole properties

- Time Dilation Calculator – Understand relativistic effects near massive objects

- Dark Matter Calculator – Explore the invisible mass shaping galaxy dynamics

- Antimatter Calculator – Calculate the energy content of matter-antimatter annihilation

- Wormhole Travel Planner – Explore theoretical spacetime shortcuts

Gravitational wave astronomy opens humanity’s ears to the cosmos. From merging black holes to the echoes of the Big Bang, spacetime ripples carry messages across billions of years, revealing the universe’s most violent and mysterious events.